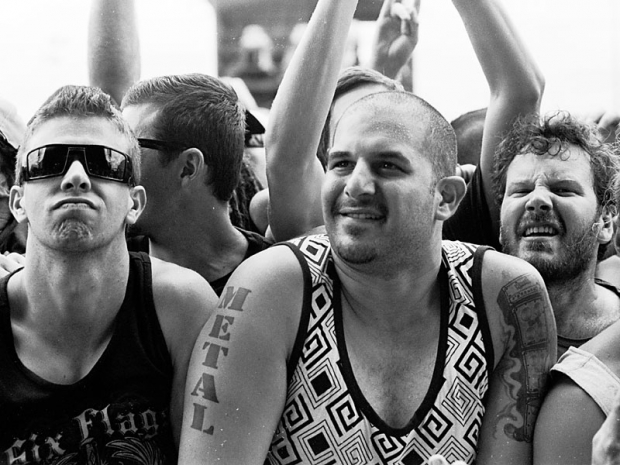

Soundwave 2014 @ RNA Showgrounds, 22.02.2014: On Film

The last festival of the summer season. Future Music happened the following week but it’s a different beast to what it’s been in the last few years, with next to no live acts and a lot more DJs and laptop acts, so I wasn’t interested in looking to photograph it.

As with Big Day Out and Laneway, these photos were taken on Kodak Tri-X pushed to ISO 800 and developed in ID-11.

Considering how many acts I shot on film at Laneway, I’m a bit surprised that I didn’t photograph very many at this year’s Soundwave. I think it was just due to time. The Laneway stages are closer together, whereas at Soundwave, especially during a period from early afternoon to early evening, there was barely enough time to photograph the bands with a digital camera, let alone have time to take some additional shots on film. Some of the acts playing during that period only got about a songs-worth of photographing before it was time to run over to another stage for another band. As we only got one song with Green Day and they didn’t tell us this until the end of the one song, there was no chance to get any film photos of the festival’s main stage headliner.

It’s a modern day music phenomena to publish a lazy post about the 10 Things We Learnt for every festival. I really hate this format of publishing for a number of reasons, and apart from being a lazy way to create content based on amalgamating a few tweeted ideas from the day, I figure that I went to school to learn and went to rock ‘n’ roll to escape all that. I don’t want to learn anything from music.

But what have I learnt from taking rolls of film at a few music festivals in 2014? The first festival I properly photographed (from the photo pit, with a photo pass, for a publication) was the first Come Together at Luna Park and I think I used about 10 rolls of film for the twenty-or-so acts I photographed. That’s 360 shots in total. The first festival I photographed with a digital camera was the first V Festival down at the Gold Coast and I only took about 500 shots during the day. Over the years there’s been a slow upwards creep in the number of photos that I take at a festival. For a while it was around the 1,000 shots mark but this year was over 1,300 shots for Big Day Out and Soundwave. That works out at 36 rolls of film, and assuming 20 bands, roughly 65 shots per band.

I know there are photographers out there who take over 4,000 photos at a typical festival, equivalent to 111 rolls of film and, assuming that 20 acts were photographed during the day, 200 shots per act on average. It seems a ludicrous amount of photos to me and I often wonder if you’re taking that many shots, how much thought is being put in to composition or looking at what’s actually happening through the viewfinder or listening to the music and anticipating what might happen next. Or are photographers just machine gunning through each band, deleting the superfluous shots at the end of the day.

There’s never been that much to music photography, even less in a digital world when you can see what you take and make adjustments to your settings and where there’s essentially no limit as to how many photos you can take. I’ve often said that I could tell someone everything I know about music photography in 15 minutes.

I really miss those heady days of a few years ago when I was one of Rave’s contributing photographers and I’d often be out 3 or 4 times a week, sometimes more, seeing some bands and photographing them. It’s one of my very favourite things to do with my time but I’ve almost always been happy to be a hobbyist photographer. There have been times when I’ve thought about how good it would be to be a professional photographer but then reality kicks in. For me, it’s never been about the money and most music photography I’ve done has been unpaid. It’s nice when someone offers you money but it’s not the be-all and end-all and not the reason I’ve ever done it. I don’t envy anyone trying to make a career as a professional photographer. Looking back on where the photography industry has gone in the last decade and projecting it forward, I can’t see it getting any better in the next ten years, let alone looking forward to the long–term future.

Throughout history technology has always usurped creative and artistic careers. Once upon a time the blacksmith was the most important person in a village and people like stone masons and thatchers were always in demand. I’m sure if you really need to find a traditional blacksmith, stone mason or thatcher, you can do but it’s a really specialised career now and (I’m guessing) comes at an appropriate price. When forums and message boards have their perennial discussions about music photography and money, I often consider that it’s like the cottage weavers against the Spinning Jennys. In a generation a craft that had existed for hundreds of years virtually disappeared. The work that was once carried out by highly skilled craftspeople could be mass produced by a machine and they were replaced by largely unskilled machine operators and manual labourers. You can’t win a battle against advanced technology. Everyone has a camera, even if it’s just the one in their pocket connected to their phone and the world is flooded with photos every minute of every hour of every day. It’s made the photograph as an item of value almost worthless. Obviously there are and there will continue to be exceptions to the rule but I wouldn’t want to be thinking of a long-term career in photography.

George Eastman’s aim was “to make the camera as convenient as the pencil” and digital photography has essentially achieved that. It’s ironic, especially given how far the technology has come in even the last 20 years, that his suicide note from 1932 was a simple “My work is done – Why wait?”

I guess this post includes some of the things I had been meaning to write in response to Leah Robertson’s ‘Guilt, Gratitude, Music Photography’ piece from last year (and also Dan Boud’s response to Leah’s article) although there’s still a lot more I could write on the subject and will no doubt get around to covering at some point in the future.

Leave a Reply